Pathways to Link Communities with Governance at the Grassroots in India

National planning takes effect and yields fruits at the grassroots. It is essential therefore to make an assessment of the efficiency of the government programs at the lower level of administration. Factual and evidence-based research will enable effective policy engagements with the district and state-level political and bureaucratic institutions for corrective measures as well as making new demands that are needed for the communities and local stakeholders. Public policy approaches to development are generally limited to levels of India and the States. Given the vast geographic expanse and high population concentrations across India a meaningful development strategy that addresses acute poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy, ill-health must occur at the level of the districts. Further, hitherto development policy decisions were made using a combination of district-level per capita averages and a small set of indicators such as average rainfall and agricultural productivity; little information on the quality of life and human development were available.

In the recent past, however, dependable data on a number of qualitative aspects of human lives have become available at the level of the district. Such data can be extracted from the decadal Census (most recent 2011), the annual national sample surveys (large sample size surveys are done at about five years intervals), and district-level household surveys. The US-India Policy Institute, Washington D. C and Centre for Research and Debates in Development Policy, New Delhi have extracted a number of socio-economic and human development indicators from multiple, nationally representative sample surveys, for all districts of India. They are reviewed to assess and compute the levels of development and equity of access to development for each district. The composite index consists of four dimensions – economic, enabling material-well being assets, education, and health. The final results in the form of maps are scheduled to be released in New Delhi in January 2015, in the form of a composite development index and four indices highlighting the components described above.

Continuing this district-level analysis, in the second stage, the development indices are computed for each of the major socio-religious communities (SRCs) for each district of the state and all districts of India. The differentials according to SRCs are presented in graphic format. This analysis is resonant with the Sachar Committee Report which was completed in 2006; the current analysis can be termed a mini-Sachar report for each district of India. In this context, there is scope to elaborate analysis of data on employment, financial allocations and measurable outcomes disaggregated by SRCs so as to operationalize policies for improving diversity in public programs. The district-level mapping and analysis for operationalizing diversity in public and private spaces cannot be over-emphasized.

Generally, the district-level reviews use service statistics drawn from district records which often are dated and qualitatively poor. The strength of the current research lies in the type and source of data as well as the methodologies used in the analysis. Information is extracted from unit (household) level records from well-respected surveys, therefore estimates are robust and academically sound. These estimates provide the academics, watchful communities, civil society, and people at large opportunities to find out the pathways to engage the district-level bureaucrats and governance.

The most important issues confronting the communities at the district level are two: a) to begin with financial allocations are inadequate; yet huge proportions of the development funds earmarked for annual expenditures on essential programs such as mass primary/elementary education, women and child development services, public healthcare and employment guarantee scheme are never appropriated and spent. b) The inequity at the level of the district is a serious issue; there are many versions to it such as based on occupations, education levels, and also social identities expressed in terms of religious and caste affiliation. The last dimension which is important at the local level in the distribution of welfare benefits; they have become contentious at the national-political level leading to the promotion of discrimination at the grassroots.

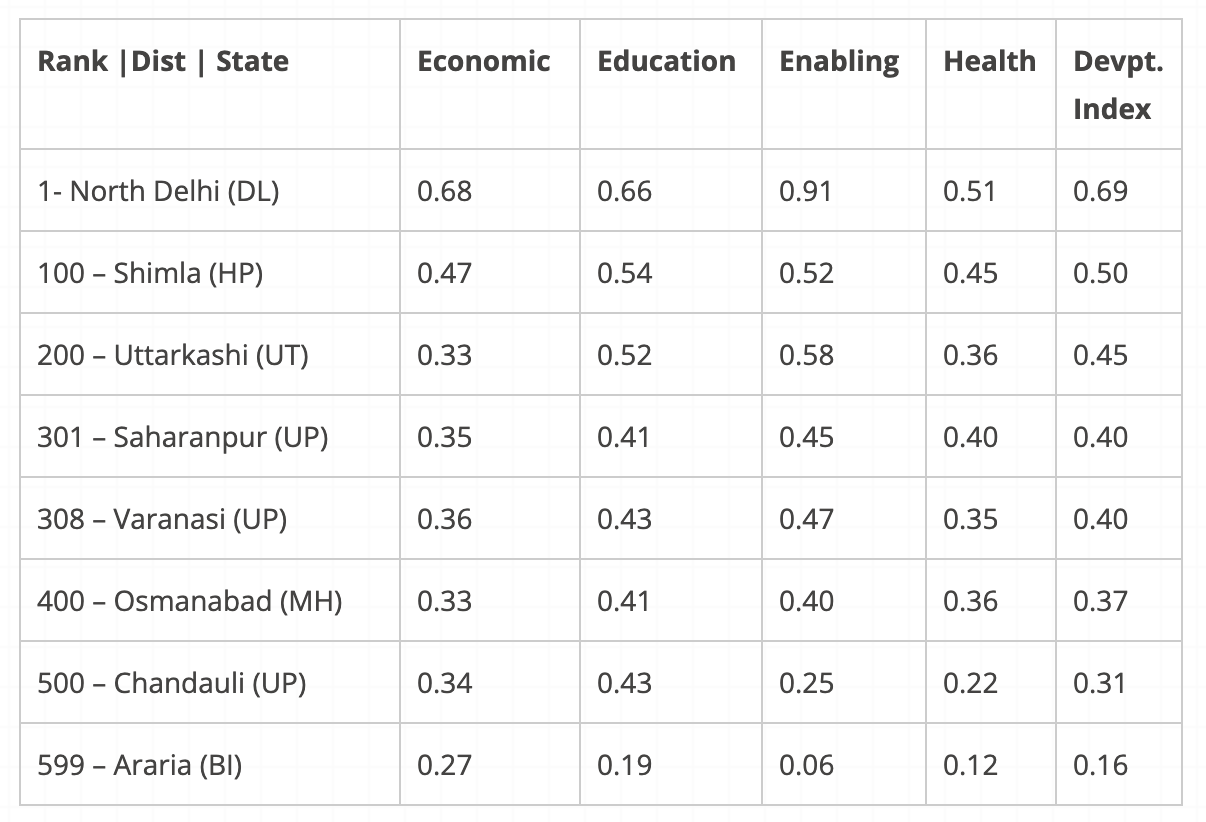

The following is a shortlist of selected districts at about one-hundredth interval. North Delhi is ranked 1 with an index of 0.69. Ideally, first rank holder could have taken a value of 1.00 but even the first district has huge scope to develop for example in health parameters which has only a value of 0.51 although the enabling index is 0.91.

However, the contrast is comparing the first ranker and the last. Araira in Bihar has recorded a development index of only 0.16 compare with North Delhi which has a value of 0.69. Note that Araira has no enabling economic environment which can push development any time near future unless critical policy strategies and investments are made soon. It is this kind of analysis both within the state and across the state which gives comprehensive information for the upliftment of communities living in clearly identified districts of India.

It is in this context that the district-level development and development index provide essential empirical evidence that makes a case for the setting up of National and State-level Equal Opportunity Commissions (EOCs). The state-level aggregated district reports will help the state government in many respects. Besides enabling assessing and monitoring of the levels of development and equity, the indices will make it easy for the state government to articulate the need to establish a ‘State Level Equal Opportunity Commission’. Such EOCs can independently deal with differentiation in access to public services at the grassroots level, thereby enabling the elected government and associated institutions to focus their time and energy on the development of the state. The EOC as an independent institution will facilitate communities and local stakeholders – civil society and private investors, to interact with each other as well as with the government bureaucracy to thrash out contentious issues and strengthen welfare policies. Further establishing State-EOCs will severe as examples for setting up a national EOC as well.

To articulate these relationships better it is essential that development practitioners, government officials, political leaders, and civil society groups come together to discuss and debate strategies to address district-level development and diversity of development. Such data will also give a comprehensive visual picture of the development of the nation from a comparative perspective promoting a strong sense of nationalism and patriotism.DDDIx makes a good case for district-level monitoring of development strategy considering the aspects of equity and social justice.